When I was a teenager, one of my best friends, Julie, lived in a rambling, slightly dishevelled house on the edge of the heath, hidden by trees. It could be a scary walk in the dark, tripping over roots and bushes and stumbling along the half mile or so of pot-holed, muddy track to the house. Julie had an older sister and parents, and a dog. Both parents have recently died, and I've been thinking about them as Christmas approaches. Christmas makes us think about families, but children need more people supporting them than just their families. They need people who supply what families don't, or can't, give.

The best, most secure moments of my teenage years were spent in a cigarette-fogged kitchen, warmed by an Aga-type stove - not in the uber-middle-class, Joanna-Trollope way, but because cutting wood from the garden and sticking it in the ancient stove was the way to keep the house warm and get the food cooked. We had long sessions of debate or emotional-outpouring fuelled by endless black coffee and an unstintingly generous supply of advice, sympathy or just listening from Anne Hughes who sat, cigarette in hand, presiding over our traumas.

She was an artist. Her fingers were often stained with paint or ink, and when they weren't, they were stained with dirt and leaf-green from the garden, and nicotine. She was slim and beautiful, with dark hair and dark eyes, and reminded me rather of Mrs Robinson in The Graduate. She never, ever belittled any teen problem brought to that kitchen. She never complained about smoking, drinking, immoderate sexual behaviour or even some of the downright stupid things we did and then suffered for. There was never a suggestion that we had brought our miseries on ourselves - or at least, not until we after we were suitably recovered.

It wasn't just a place for miseries. We talked about poetry and books and art. We planned trips to the Tate, we cooked (probably horrid) meals and 'treats', and we even dabbled in witchcraft. (I remember one spell to bring a desired boy to one at midnight. Curiously, it worked. The boy was found by my dad wandering around our garden, three miles from his home, unable to say why he was there. That put us off witching.) People pierced each other's ears, dyed their hair, painted each other/themselves with henna and made various kinds of music, usually involving a number of guitars and anything else that was lying around. We wrote maudlin poems and sweet songs. The door was always open, no one was ever turned away, the biscuit tin was never empty and the coffee flowed like 2012-floodwater. Mrs Hughes frequently entertained both partners in a floundering romance, and her discretion was beyond doubt so that was fine.

My own parents preferred a clean, tidy house, not cluttered with teens who didn't belong there and hadn't been specifically invited. They didn't like music, they didn't drink or smoke or do any drugs, or tolerate any of those things. They had little in the way of aesthetic sense and very little inclination for emotional intimacy with anyone else (except the next-door neighbour). There were, in fact, quite good reasons for all this, but I didn't know them at the time, so they didn't count. In effect, Anne and Tom Hughes were the parents I would have had if I could have chosen my own. But it would have been the wrong choice. They were brilliant, and an essential part of my young life precisely because they weren't my own parents. Because they had no investment in my existential angst or silly mistakes, their kindness was freely given; it was not part of the parenting bargain and it could not be clouded later by resentment or reproof. They gave me kindness I was not 'entitled' to - and so gave me an even more valuable gift: acceptance, which every teen needs.

And, beyond that, a model of the best way to be. I haven't lived up to Anne Hughes' standard. But I have tried to be like her to my daughters' friends. I am the go-to person for pregnancy tests, for looking after those too drunk to go home, for advice about embarrassing medical issues or drug problems, or lifts to A&E, or a large glass of wine and a pile of tissues. And I think many of us who passed through her kitchen have done the same - taken a tiny bit of what she was and tried to live it. Inadequately, perhaps, but it's better than nothing. That's how she lives on. Thank you, Anne Hughes, for everything. Rest in peace.

This blog started as a guide to publishing and if you look through the old stuff there's plenty of advice that is still useful. Now it's more random ruminations and pointless pontificating around publishing

Tuesday, 25 December 2012

Sunday, 23 December 2012

Had we but world enough and time....

This coyness, story, were no crime.

But we don't have world enough and time. We have deadlines. And a story that slips in and out of view, dragging its characters into dark corners and throwing out an enticing distraction, is apt to get abandoned for another commission.

Stories take time. And they don't just take time to write, they take time to stalk and to understand. The time spent actually writing a picture book might be only a day or even less (though sometimes it's much longer), but the total time it takes can be months or even years. For longer books, it's much more complicated. There are stages to even the simplest book:

I had a few weeks between other books in the autumn and tried to bully these into shape. But they just hadn't had their composting time. If you get all the old potato peelings out of your compost bin and spread them on the garden, it's not going to do any good. Patience. It takes time for the subconscious to work, like worms, on the idea-mulch. It's too frustrating. I want to play with them NOW.

But we don't have world enough and time. We have deadlines. And a story that slips in and out of view, dragging its characters into dark corners and throwing out an enticing distraction, is apt to get abandoned for another commission.

Stories take time. And they don't just take time to write, they take time to stalk and to understand. The time spent actually writing a picture book might be only a day or even less (though sometimes it's much longer), but the total time it takes can be months or even years. For longer books, it's much more complicated. There are stages to even the simplest book:

- inspiration - that moment when the idea comes to you. It might come as a story, a character, a plot idea, a situation, even a snatch of dialogue or the first line. That's just the seed, though. (Which is why it's so frustrating when non-writers say 'I've got a great idea for a book... perhaps you'd like to write it and we can share the money?' Yeah, I've got a bag of lawn seed. Perhaps you'd like to plant it, grow and nurture the lawn, and then we can play croquet on it.

- working it into a proper idea - people do varying amounts of planning, but even if you don't write a plan the idea needs to compost into something you can work with

- writing the damn thing - putting the ideas into words is always the point where the instance varies from the ideal form - where your perfectly conceived book becomes an inadequate pile of words that doesn't quite capture it. Fun and frustrating in varying measures

- realising it's crap and despairing - just wait

- rewriting/editing to make it a bit less crap. Repeat until relatively uncrappy.

I had a few weeks between other books in the autumn and tried to bully these into shape. But they just hadn't had their composting time. If you get all the old potato peelings out of your compost bin and spread them on the garden, it's not going to do any good. Patience. It takes time for the subconscious to work, like worms, on the idea-mulch. It's too frustrating. I want to play with them NOW.

Saturday, 15 December 2012

Who pays the piper?

This post will make me unpopular. I await the brickbats.

Before we start, though, I would say that this post is in NO WAY critical of the friend whose remark sparked it. This has been my view for years, she just reminded me of it, and how it is a more important issue now with such massive public spending cuts.

I don't approve of Arts Council grants to writers. There. I've said it. The public purse should not - as a rule - fund the personal ambition of people who want to write fiction, poetry, or non-fiction.

I'm not against public funding of the arts - I see no problem in funding projects where the intended beneficiary is the public - but I don't see a grant to finish a novel as benefiting the public. The public doesn't need another novel, there are already plenty. A community might need a theatre, or an art gallery, or subsidised tickets to performances, but arts funding should be targeted at the general good and not at individual authors in need of money. Notice I say 'as a rule' - there will always be a few exceptions. But this is about the majority of cases.

A couple of weeks ago, I was having coffee with a very good friend, an award-winning writer in an area that generates virtually no income, who is now writing in a different genre. Let's call her Kate. She had been advised to apply for an Arts Council grant and we were talking about whether or not she should do so. She asked if I'd ever applied and if I ever would, and I'd said 'no' to both questions.

'But it's different for you,' she said. 'You get paid for what you write.' I accepted that and we moved on.

But that came back to me later. I do get paid for what I write. Or, rather, I write what I get paid for. I talk to publishers and my agent about what publishers want. I take almost any commission that comes my way (these days - in the past there were often too many and I turned away those I liked less). When there is not enough writing to be paid for I build websites, make book trailer videos, teach creative writing... do other things that pay.

I will write on subjects I'm not hugely attracted to and for markets I'm not keen on, because I have to put food on the table and writing is my job. If I were a doctor who specialised in fractures, I couldn't say 'I won't do broken arms, they're boring. Bring me only broken legs.' If you have a job, you have to do the less interesting bits as well as the exciting bits. That's how you earn enough to live on. If you want to be precious about your writing, that's fine, but don't expect the rest of us to pay to keep you pure.

Why, at a time when there are people without enough to live on, should the public purse fund someone who wants to write a book? It's not as though there is a world shortage of books. This is not a case of people who can't find a job asking for unemployment benefit. It's a case of people who will probably write a book anyway, though possibly more slowly without the funding, asking for public money to write it now.

I know Kate's book will take a lot of research. I know it will probably win awards when it is published. That's not the case for all books funded by Arts Council grants - some won't even find a publisher. I don't see why my friend working in Waitrose and doing a degree while building his band in his free time, or his friend in Waitrose who is establishing himself as an illustrator, should subsidise people who want to short-circuit the struggle and be paid from the public purse to write.

This year, I've been writing a couple of books for which I have no contract. I write them when I have time, and they would go a lot better and more quickly if I didn't have to keep earning money at the same time. That's why it's a good idea to get a contract and advance. These are in short supply - I know, that's why I haven't got one. (Or maybe because the books aren't good enough, or because I haven't approached any publishers yet with these half-baked ideas.)

If a writer produces books that sell, the publishing industry should work in such a way that the writer is adequately paid for their work. That's not always the case - but that's a problem we have to tackle within the industry. In times of plenty, society can perhaps afford to subsidise writers - but not now. Not when benefits are being cut to the bone, when more than 100,000 people in the UK rely on food banks, libraries are closing and schools can't afford books or teachers. Yes, if we collected the taxes we are rightly owed, we wouldn't need cuts. But now - right NOW - the money isn't there. So let's spend what there is on things that really matter. And that isn't one more untried novel.

* * * * *

For the record, I have no problem with charities supporting writers (the people who give to or endow those charities have chosen to spend their money in that way). And I don't think my view automatically extends to all forms of art. A cellist, for example, needs to keep practising at a high level to secure their skill for the future. A writer can take a break or work slowly with no real detriment. And anyone - really, anyone - can find some time to write if they really want to. But time and writers is another rant, for another day.

STOP PRESS: catdownunder has carried the debate to Australia on her own blog so please do take a look at her points and commenters.

Before we start, though, I would say that this post is in NO WAY critical of the friend whose remark sparked it. This has been my view for years, she just reminded me of it, and how it is a more important issue now with such massive public spending cuts.

I don't approve of Arts Council grants to writers. There. I've said it. The public purse should not - as a rule - fund the personal ambition of people who want to write fiction, poetry, or non-fiction.

I'm not against public funding of the arts - I see no problem in funding projects where the intended beneficiary is the public - but I don't see a grant to finish a novel as benefiting the public. The public doesn't need another novel, there are already plenty. A community might need a theatre, or an art gallery, or subsidised tickets to performances, but arts funding should be targeted at the general good and not at individual authors in need of money. Notice I say 'as a rule' - there will always be a few exceptions. But this is about the majority of cases.

A couple of weeks ago, I was having coffee with a very good friend, an award-winning writer in an area that generates virtually no income, who is now writing in a different genre. Let's call her Kate. She had been advised to apply for an Arts Council grant and we were talking about whether or not she should do so. She asked if I'd ever applied and if I ever would, and I'd said 'no' to both questions.

'But it's different for you,' she said. 'You get paid for what you write.' I accepted that and we moved on.

But that came back to me later. I do get paid for what I write. Or, rather, I write what I get paid for. I talk to publishers and my agent about what publishers want. I take almost any commission that comes my way (these days - in the past there were often too many and I turned away those I liked less). When there is not enough writing to be paid for I build websites, make book trailer videos, teach creative writing... do other things that pay.

I will write on subjects I'm not hugely attracted to and for markets I'm not keen on, because I have to put food on the table and writing is my job. If I were a doctor who specialised in fractures, I couldn't say 'I won't do broken arms, they're boring. Bring me only broken legs.' If you have a job, you have to do the less interesting bits as well as the exciting bits. That's how you earn enough to live on. If you want to be precious about your writing, that's fine, but don't expect the rest of us to pay to keep you pure.

Why, at a time when there are people without enough to live on, should the public purse fund someone who wants to write a book? It's not as though there is a world shortage of books. This is not a case of people who can't find a job asking for unemployment benefit. It's a case of people who will probably write a book anyway, though possibly more slowly without the funding, asking for public money to write it now.

I know Kate's book will take a lot of research. I know it will probably win awards when it is published. That's not the case for all books funded by Arts Council grants - some won't even find a publisher. I don't see why my friend working in Waitrose and doing a degree while building his band in his free time, or his friend in Waitrose who is establishing himself as an illustrator, should subsidise people who want to short-circuit the struggle and be paid from the public purse to write.

This year, I've been writing a couple of books for which I have no contract. I write them when I have time, and they would go a lot better and more quickly if I didn't have to keep earning money at the same time. That's why it's a good idea to get a contract and advance. These are in short supply - I know, that's why I haven't got one. (Or maybe because the books aren't good enough, or because I haven't approached any publishers yet with these half-baked ideas.)

If a writer produces books that sell, the publishing industry should work in such a way that the writer is adequately paid for their work. That's not always the case - but that's a problem we have to tackle within the industry. In times of plenty, society can perhaps afford to subsidise writers - but not now. Not when benefits are being cut to the bone, when more than 100,000 people in the UK rely on food banks, libraries are closing and schools can't afford books or teachers. Yes, if we collected the taxes we are rightly owed, we wouldn't need cuts. But now - right NOW - the money isn't there. So let's spend what there is on things that really matter. And that isn't one more untried novel.

* * * * *

For the record, I have no problem with charities supporting writers (the people who give to or endow those charities have chosen to spend their money in that way). And I don't think my view automatically extends to all forms of art. A cellist, for example, needs to keep practising at a high level to secure their skill for the future. A writer can take a break or work slowly with no real detriment. And anyone - really, anyone - can find some time to write if they really want to. But time and writers is another rant, for another day.

STOP PRESS: catdownunder has carried the debate to Australia on her own blog so please do take a look at her points and commenters.

Friday, 30 November 2012

Return to Captcha

Sadly, after a brief flirtation with free love, I've returned the Captcha comment verification to the blog. There were not too many spam comments to start with, but they have mushroomed over the last week and far more were getting through Blogger's spam filter. I don't have time to be deleting crud from the comments all the time. Interestingly, the post that attracts by far the most spam is PLR =/= income tax (a curmudgeonly rant) presumably because PLR and income tax and search-magnets.

Scanning the spam, though, I did wonder about some of the comments. Why is the word 'fastidious' so common in them? Who ever follows those links anyway? But who in particular is going to follow a link if the comment starts off 'most of the people who comment here appear brain dead' or 'I was hoping to find something interesting here, not a lot of complaining about a problem you could do something about if you would just stop complaining'? (The latter might be appropriate to one or two of my rants, but it wasn't appropriate to the cheerful post it was attached to.)

Spam-mongers are, I suppose, the cold-callers of the blogosphere. But if I were a robot, I'd go and look for a job building car bodies or something instead of leaving comments on random blogs. (Yes, I do know it's a different type of robot. Joke. Don't flood me with comments about bots/robots and software/hardware. Especially not spam comments.)

And finally... the hits on the blog have rocketed up with captcha turned off. I suspect this means the bots are hunting out blogs without verification. So if any of you wants just numbers of hits, so that you can brag to a publisher that your blog gets 10,000 hits a month, or whatever, just turn off captcha and wait a few weeks. And if you're a publisher, and some prospective writer tells you their blog gets 10,000 hits a month, just pop along there and see if comment verification is turned on. If not, lots of those hits are from bots that won't buy a book.

So I'm very sorry about the return to the stupid letter/number reading and I know they are very hard to do. But please carry on leaving comments. As the other bots say: your comment is valuable to us so please continue to hold.

Scanning the spam, though, I did wonder about some of the comments. Why is the word 'fastidious' so common in them? Who ever follows those links anyway? But who in particular is going to follow a link if the comment starts off 'most of the people who comment here appear brain dead' or 'I was hoping to find something interesting here, not a lot of complaining about a problem you could do something about if you would just stop complaining'? (The latter might be appropriate to one or two of my rants, but it wasn't appropriate to the cheerful post it was attached to.)

Spam-mongers are, I suppose, the cold-callers of the blogosphere. But if I were a robot, I'd go and look for a job building car bodies or something instead of leaving comments on random blogs. (Yes, I do know it's a different type of robot. Joke. Don't flood me with comments about bots/robots and software/hardware. Especially not spam comments.)

And finally... the hits on the blog have rocketed up with captcha turned off. I suspect this means the bots are hunting out blogs without verification. So if any of you wants just numbers of hits, so that you can brag to a publisher that your blog gets 10,000 hits a month, or whatever, just turn off captcha and wait a few weeks. And if you're a publisher, and some prospective writer tells you their blog gets 10,000 hits a month, just pop along there and see if comment verification is turned on. If not, lots of those hits are from bots that won't buy a book.

So I'm very sorry about the return to the stupid letter/number reading and I know they are very hard to do. But please carry on leaving comments. As the other bots say: your comment is valuable to us so please continue to hold.

Wednesday, 21 November 2012

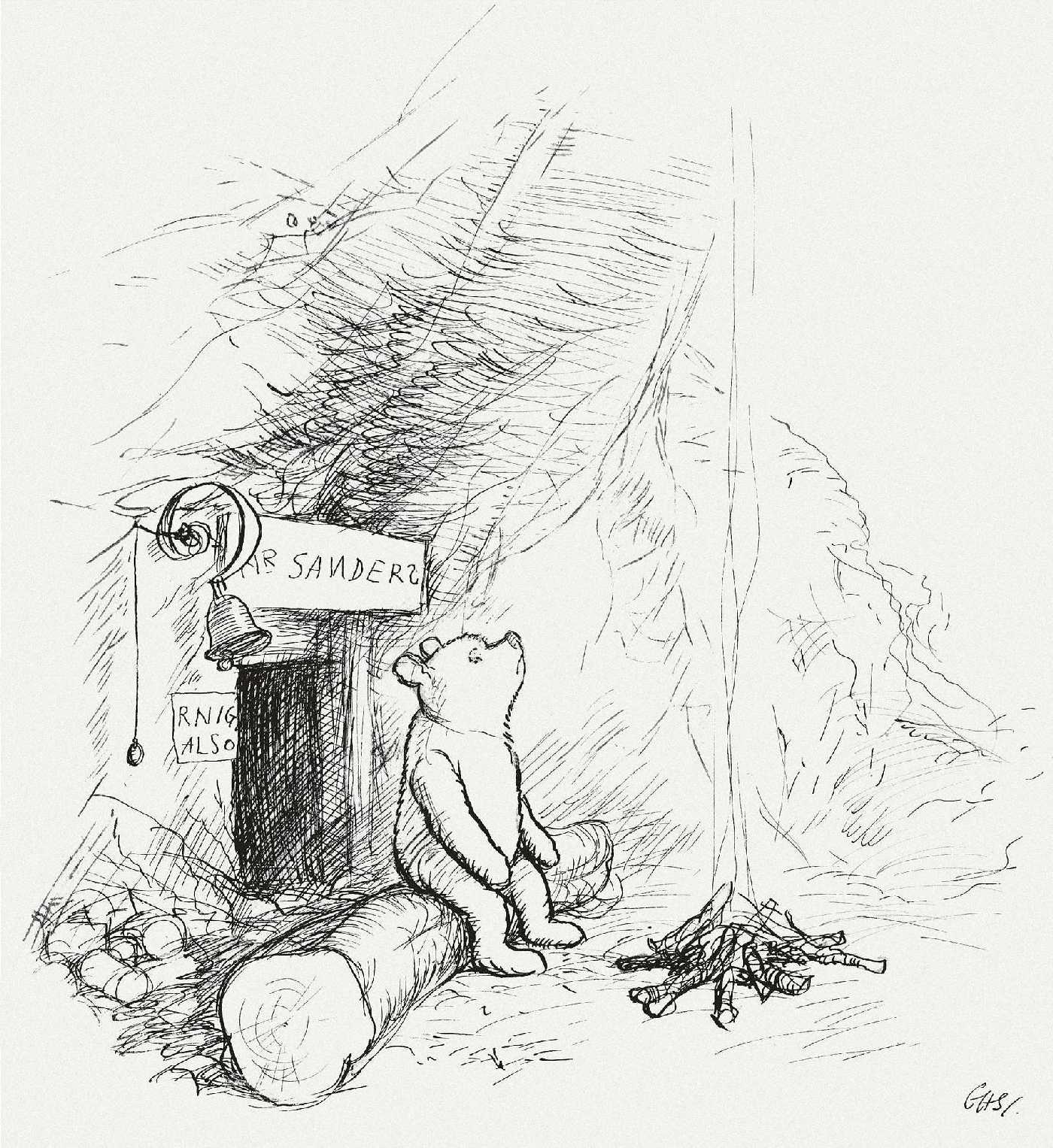

The other place: Book vivisection

Nothing new here today, but Winnie-the-Pooh is dissected with a sharp scalpel over at Stroppy's second home, Book Vivisection.

Thursday, 15 November 2012

Working premises

Today we're going to talk about premises. Not the building you write in, but the central idea behind a story.

Creative writing students and new writers often have real difficulty with identifying the premise of their story. Sometimes that's because they don't have one, or the premise is so weak it won't support much of a story. But often it's because they don't really understand what a premise is.

The premise is similar to the hook, or the one-line pitch, except the point of it is not to sell your story, but to provide its backbone.

If your story has no premise, it's like a jellyfish, just flobbling around with no direction or plan in life (apologies to jellyfish who feel undermined by this assessment of their prospects).

If it has a strong premise and everything sticks firmly to it, with no extraneous curfuffle, it's like a strong, sleek snake.

Most stories are somewhere in between, with a premise but some things (subplots, for example) which branch out from it. But they should branch - they should not float around, only held in the body of the work by the soft tissue.

This is a whale. It has a vestigial leg, the only purpose of which is to prove that evolution is true. It is not connected to the whale's backbone. Make sure your story doesn't have vestigial legs.

Some stories have a premise which doesn't really lend itself to narrative, which is a bit of a shame.

Black Beauty is an example. The premise is 'horses suffer at the hands of humans and there's nothing they can do about it.' So that sets us up with a central character who has no autonomy, but will be buffeted by fate (in the form of capricious humans) and we will just have to see whether he responds by being stalwart and heroic or by being rebellious - and more than likely sent to the knacker's yard as a consequence. It's a moral fable, and a didactic treatise on horse-management. In terms of narrative, it's a series of loosely connected episodes, of the 'and then...and then... and then...' type, some of them with an explicit moral chucked in. (Keep Sundays sacred, don't drink, etc.) This is, as Mary Hoffman pointed out to me, the structure of the misery memoir. I would add: or the saint's life. Hagiography of a horse.

Black Beauty is an example. The premise is 'horses suffer at the hands of humans and there's nothing they can do about it.' So that sets us up with a central character who has no autonomy, but will be buffeted by fate (in the form of capricious humans) and we will just have to see whether he responds by being stalwart and heroic or by being rebellious - and more than likely sent to the knacker's yard as a consequence. It's a moral fable, and a didactic treatise on horse-management. In terms of narrative, it's a series of loosely connected episodes, of the 'and then...and then... and then...' type, some of them with an explicit moral chucked in. (Keep Sundays sacred, don't drink, etc.) This is, as Mary Hoffman pointed out to me, the structure of the misery memoir. I would add: or the saint's life. Hagiography of a horse.

Some stories have a premise with strong narrative potential. The premise of The Hunger Games is that in a future dystopian society, the ruling group keep control by forcing children to kill each other in a reality TV show. The reality-TV-show element has particular resonance for our society because so many of us sit glued to reality TV shows every week, but the central idea of the child sacrifice to keep society in order is as old as the minotaur legend it draws on, and older. (Indeed, I'd say it's a version of what all societies do in trying to maintain the status quo, but that's a digression.)

If you can frame your premise as a fairly precise and interesting question that can have more than one answer,and that contains the germ of a conflict or challenge, you have a strong premise with narrative potential. So 'what would happen if a Minoan-style sacrifice were demanded of a modern/future society?' works. I'd say 'what happens if you're a horse?' is not a good premise. It's too vague, and although there are lots of specific answers, there is really only one over-arching answer, and it's that things happen to you.

A story with a strong premise can be fixed. A story with a weak premise, or no premise, is doomed (in today's market - don't write Black Beauty, it's not 1877). Work out your premise before you spend months writing the story - you might be wasting your time.

Do you know what the premise of your story is? Don't say 'it's about a boy who goes on an adventure...' That's a plot summary. What is the question that your book answers? By the way, the question will also tell you whether your book is that elusive thing, 'high concept'. What is the question, and what is the answer? That is your book, in a nutshell: the question is the premise and the answer is the plot. If there is no interesting question, or no plausible or interesting answer, you might like to think again...

Creative writing students and new writers often have real difficulty with identifying the premise of their story. Sometimes that's because they don't have one, or the premise is so weak it won't support much of a story. But often it's because they don't really understand what a premise is.

The premise is similar to the hook, or the one-line pitch, except the point of it is not to sell your story, but to provide its backbone.

|

| Moon jellyfish, Hans Hillewaert |

If your story has no premise, it's like a jellyfish, just flobbling around with no direction or plan in life (apologies to jellyfish who feel undermined by this assessment of their prospects).

|

| Snake skeletong, dbking |

If it has a strong premise and everything sticks firmly to it, with no extraneous curfuffle, it's like a strong, sleek snake.

Most stories are somewhere in between, with a premise but some things (subplots, for example) which branch out from it. But they should branch - they should not float around, only held in the body of the work by the soft tissue.

This is a whale. It has a vestigial leg, the only purpose of which is to prove that evolution is true. It is not connected to the whale's backbone. Make sure your story doesn't have vestigial legs.

Some stories have a premise which doesn't really lend itself to narrative, which is a bit of a shame.

Black Beauty is an example. The premise is 'horses suffer at the hands of humans and there's nothing they can do about it.' So that sets us up with a central character who has no autonomy, but will be buffeted by fate (in the form of capricious humans) and we will just have to see whether he responds by being stalwart and heroic or by being rebellious - and more than likely sent to the knacker's yard as a consequence. It's a moral fable, and a didactic treatise on horse-management. In terms of narrative, it's a series of loosely connected episodes, of the 'and then...and then... and then...' type, some of them with an explicit moral chucked in. (Keep Sundays sacred, don't drink, etc.) This is, as Mary Hoffman pointed out to me, the structure of the misery memoir. I would add: or the saint's life. Hagiography of a horse.

Black Beauty is an example. The premise is 'horses suffer at the hands of humans and there's nothing they can do about it.' So that sets us up with a central character who has no autonomy, but will be buffeted by fate (in the form of capricious humans) and we will just have to see whether he responds by being stalwart and heroic or by being rebellious - and more than likely sent to the knacker's yard as a consequence. It's a moral fable, and a didactic treatise on horse-management. In terms of narrative, it's a series of loosely connected episodes, of the 'and then...and then... and then...' type, some of them with an explicit moral chucked in. (Keep Sundays sacred, don't drink, etc.) This is, as Mary Hoffman pointed out to me, the structure of the misery memoir. I would add: or the saint's life. Hagiography of a horse. Some stories have a premise with strong narrative potential. The premise of The Hunger Games is that in a future dystopian society, the ruling group keep control by forcing children to kill each other in a reality TV show. The reality-TV-show element has particular resonance for our society because so many of us sit glued to reality TV shows every week, but the central idea of the child sacrifice to keep society in order is as old as the minotaur legend it draws on, and older. (Indeed, I'd say it's a version of what all societies do in trying to maintain the status quo, but that's a digression.)

If you can frame your premise as a fairly precise and interesting question that can have more than one answer,and that contains the germ of a conflict or challenge, you have a strong premise with narrative potential. So 'what would happen if a Minoan-style sacrifice were demanded of a modern/future society?' works. I'd say 'what happens if you're a horse?' is not a good premise. It's too vague, and although there are lots of specific answers, there is really only one over-arching answer, and it's that things happen to you.

A story with a strong premise can be fixed. A story with a weak premise, or no premise, is doomed (in today's market - don't write Black Beauty, it's not 1877). Work out your premise before you spend months writing the story - you might be wasting your time.

Do you know what the premise of your story is? Don't say 'it's about a boy who goes on an adventure...' That's a plot summary. What is the question that your book answers? By the way, the question will also tell you whether your book is that elusive thing, 'high concept'. What is the question, and what is the answer? That is your book, in a nutshell: the question is the premise and the answer is the plot. If there is no interesting question, or no plausible or interesting answer, you might like to think again...

Monday, 29 October 2012

How to speak publisher: F is for Flat fee

Everyone knows how books work. You have a great idea, write a synopsis and a couple of chapters (or all of it), send it off to a publisher (or twenty), sign a contract, get the first chunk of the massive (or tiny) advance, sit down to write the book, get the next chunk of advance, argue about a few changes, get the last chunk of advance, and watch your book walk (or crawl) off the shelves while you wait for your first royalty cheque (after it earns out, of course).

Alternatively....

Sit at home looking at your email until a publisher asks you to write a book. Send in a synopsis, get first chunk of small (or large - not unheard of) fee, write book, get second chunk of fee, argue about changes to keep it in line with rest of series, get the last chunk of fee and expunge book from your memory totally while waiting for the next email from a publisher. It's more like a series of one-night-stands than a proper relationship; writing whore rather than the kept mistress of RandomPenguin (or wherever).

Lots of books are written for a flat fee, especially in children's publishing. Typically, you might be offered a flat fee for children's non-fiction (any market from textbook to mass market); reading scheme books for the schools market; licensed character books (those about established characters such as Wallace and Gromit or Disney mice); and character-led fiction that's part of a series written by many authors and published under a pseudonym that reflects the genre (eg Carnivorous d'Vil or Tinsel Rosebottom). You could can get a royalty deal on all these from some publishers - but a flat fee is fairly typical.

There are obvious advantages for publishers in paying a flat fee: they know how much they have to pay; there is none of that complicated looking at the spreadsheet to see how much to pay you in royalties; if your book is a mega-hit, they keep all the profit; it makes their budgeting easy.

There are less obvious disadvantages for publishers: it makes no material difference to you whether the book sells, so you won't do much publicity; they certainly can't expect you to do any visits or signings or anything for free as increasing the sales of the book does you no good (except for BookScan figures, but they don't really count for much in these particular markets). If a book is really successful, the writer won't want to write for you again on a flat fee basis as they will suppose (or imagine) they can earn more writing for another publisher who will pay a royalty.

There are obvious disadvantages for the writer: if your book sells 100,000+ copies you still don't get any more than the flat fee (been there). You won't know what the sales figures are - this might sound unimportant, but it's not. If you want to pitch an idea to another publisher, it can be very useful to be able to say a previous title sold 100,000 copies. Of course, the publisher can check that figure, but you can't! (Unless you pay Neilsen for the info.) And because you can't, you won't know which book to list as your mega-seller.

But there are also less obvious advantages for the writer: you don't need to keep checking sales rank on Amazon, look for reviews or worry about whether the book is in the shops; you don't have to do visits and signings (unless you like that sort of thing); your mind is free to work on the next book; you can do your budgeting with confidence; the flat fee is likely to be more than the advance you would have got for the same book. A book with a small advance that doesn't earn out will generally pay you less than the same book for a flat fee. If you want money now to pay to feed your children and pay the broadband bill, flat fee is often the more attractive option. It's not selling out, it's pragmatism.

Often, but not always, a flat fee is offered when the book is the publisher's idea. There is a certain fairness to this - the book would be written whether you wrote it or not. Maybe not as well, but frankly it's not going to sell on quality, is it? If a kid wants the next Vampire ballerinas book, they'll buy it anyway. As long as the flat fee is fixed with a realistic and fair assessment of the likely sales, it is usually a reasonable way to operate. The author should get as much as they would get in total royalties if it were a royalty deal.

Of course, there are rogue publishers who try to get away with flat fee offers of £200 or some such. Good, professional writers turn them down, but probably somewhere an aspiring writer will take the deal. And it takes guts to turn down anything when you don't have the next mortgage payment in the bank. (If the publisher is small and can't afford a decent fee, that's no excuse for offering £200 - they should at least make the £200 an advance and give a decent royalty; then it's up to the writer whether they trust their work and the publishers' distribution enough to give it a go.)

Flat fee is often 'work for hire' in legal terms. The publisher frequently wants to buy out the copyright and will often try to get you to waive your moral rights as well. The general advice is never to sell copyright, only to licence it. Whether you will get that through depends on the type of book and the publisher. (And how much you are prepared to dig your heels in.)

Imagine a publisher has a series of books about vegetables. They have asked you to write the Potatoes title. You want to keep the copyright. They will find someone else. Any competent writer can write about potatoes. Maybe some won't do it quite as well as you will, but the book will still be done and the editor can make it good enough. The publisher doesn't need to give way on the copyright issue.

Now imagine a publisher has a series of early reader fiction for sale into schools. They have asked you to write some animal stories. The plot and characters are up to you, they just have to be about animals, be 500 words long and divide into 12 spreads. You want to keep the copyright. This is a harder thing to do well, so the publishers might well agree. There is no end of people who will claim they can write animal stories 500 words long, but most of those stories will be rubbish. It's not like potatoes. (By the way, I have done both of these, and so feel quite free to diss the potato-writing aspect. Although actually I didn't do the potato title, so maybe that one was harder than carrots.)

If you can keep copyright, do so. For one thing, if the publisher goes bust you should be able to claim your title back and publish it elsewhere [hollow laughter] or make an ebook [unless it's illustrated, not by you]. I always cross out moral rights waiver if my name will be on the book (if your name's not going to be on it anyway - as in licensed character work - the moral rights are of no value to you).

As for the one real injustice - the 100,000+ sales because you did the book so well - my solution to that one was to negotiate with the publisher to add a royalty clause to all future contracts that kicks in if sales go over 100,000. They are content with that - if the book sells that many copies, they can afford the royalty, and if it doesn't they've not lost anything.

Alternatively....

Sit at home looking at your email until a publisher asks you to write a book. Send in a synopsis, get first chunk of small (or large - not unheard of) fee, write book, get second chunk of fee, argue about changes to keep it in line with rest of series, get the last chunk of fee and expunge book from your memory totally while waiting for the next email from a publisher. It's more like a series of one-night-stands than a proper relationship; writing whore rather than the kept mistress of RandomPenguin (or wherever).

Lots of books are written for a flat fee, especially in children's publishing. Typically, you might be offered a flat fee for children's non-fiction (any market from textbook to mass market); reading scheme books for the schools market; licensed character books (those about established characters such as Wallace and Gromit or Disney mice); and character-led fiction that's part of a series written by many authors and published under a pseudonym that reflects the genre (eg Carnivorous d'Vil or Tinsel Rosebottom). You could can get a royalty deal on all these from some publishers - but a flat fee is fairly typical.

There are obvious advantages for publishers in paying a flat fee: they know how much they have to pay; there is none of that complicated looking at the spreadsheet to see how much to pay you in royalties; if your book is a mega-hit, they keep all the profit; it makes their budgeting easy.

There are less obvious disadvantages for publishers: it makes no material difference to you whether the book sells, so you won't do much publicity; they certainly can't expect you to do any visits or signings or anything for free as increasing the sales of the book does you no good (except for BookScan figures, but they don't really count for much in these particular markets). If a book is really successful, the writer won't want to write for you again on a flat fee basis as they will suppose (or imagine) they can earn more writing for another publisher who will pay a royalty.

There are obvious disadvantages for the writer: if your book sells 100,000+ copies you still don't get any more than the flat fee (been there). You won't know what the sales figures are - this might sound unimportant, but it's not. If you want to pitch an idea to another publisher, it can be very useful to be able to say a previous title sold 100,000 copies. Of course, the publisher can check that figure, but you can't! (Unless you pay Neilsen for the info.) And because you can't, you won't know which book to list as your mega-seller.

But there are also less obvious advantages for the writer: you don't need to keep checking sales rank on Amazon, look for reviews or worry about whether the book is in the shops; you don't have to do visits and signings (unless you like that sort of thing); your mind is free to work on the next book; you can do your budgeting with confidence; the flat fee is likely to be more than the advance you would have got for the same book. A book with a small advance that doesn't earn out will generally pay you less than the same book for a flat fee. If you want money now to pay to feed your children and pay the broadband bill, flat fee is often the more attractive option. It's not selling out, it's pragmatism.

Often, but not always, a flat fee is offered when the book is the publisher's idea. There is a certain fairness to this - the book would be written whether you wrote it or not. Maybe not as well, but frankly it's not going to sell on quality, is it? If a kid wants the next Vampire ballerinas book, they'll buy it anyway. As long as the flat fee is fixed with a realistic and fair assessment of the likely sales, it is usually a reasonable way to operate. The author should get as much as they would get in total royalties if it were a royalty deal.

Of course, there are rogue publishers who try to get away with flat fee offers of £200 or some such. Good, professional writers turn them down, but probably somewhere an aspiring writer will take the deal. And it takes guts to turn down anything when you don't have the next mortgage payment in the bank. (If the publisher is small and can't afford a decent fee, that's no excuse for offering £200 - they should at least make the £200 an advance and give a decent royalty; then it's up to the writer whether they trust their work and the publishers' distribution enough to give it a go.)

Flat fee is often 'work for hire' in legal terms. The publisher frequently wants to buy out the copyright and will often try to get you to waive your moral rights as well. The general advice is never to sell copyright, only to licence it. Whether you will get that through depends on the type of book and the publisher. (And how much you are prepared to dig your heels in.)

Imagine a publisher has a series of books about vegetables. They have asked you to write the Potatoes title. You want to keep the copyright. They will find someone else. Any competent writer can write about potatoes. Maybe some won't do it quite as well as you will, but the book will still be done and the editor can make it good enough. The publisher doesn't need to give way on the copyright issue.

Now imagine a publisher has a series of early reader fiction for sale into schools. They have asked you to write some animal stories. The plot and characters are up to you, they just have to be about animals, be 500 words long and divide into 12 spreads. You want to keep the copyright. This is a harder thing to do well, so the publishers might well agree. There is no end of people who will claim they can write animal stories 500 words long, but most of those stories will be rubbish. It's not like potatoes. (By the way, I have done both of these, and so feel quite free to diss the potato-writing aspect. Although actually I didn't do the potato title, so maybe that one was harder than carrots.)

If you can keep copyright, do so. For one thing, if the publisher goes bust you should be able to claim your title back and publish it elsewhere [hollow laughter] or make an ebook [unless it's illustrated, not by you]. I always cross out moral rights waiver if my name will be on the book (if your name's not going to be on it anyway - as in licensed character work - the moral rights are of no value to you).

As for the one real injustice - the 100,000+ sales because you did the book so well - my solution to that one was to negotiate with the publisher to add a royalty clause to all future contracts that kicks in if sales go over 100,000. They are content with that - if the book sells that many copies, they can afford the royalty, and if it doesn't they've not lost anything.

Monday, 22 October 2012

How are we doing? Or, reasons to be cheerful...

There is a lot of doom and gloom amongst British children's authors at the moment - and with good cause. But an interesting bestsellers list in (of all places) the Daily Mail offers some solace. It lists the fifty best-selling authors. Number one is JK Rowling (no surprise there); then come Jamie Oliver, James Patterson, Terry Pratchett and Jacqueline Wilson. So four of the top five are UK writers, and half are children's writers (I'm putting Pratchett in both camps).

Thirty-five out of fifty are British. Fourteen (thirteen and two halves) of those write for children - fifteen if we include the one who writes GCSE guides. So of all the books in all the world (well, probably the English-speaking world), 15 out of 50 bestselling writers write for children and are British. (There is also Stephanie Meyer, and possibly some foreign ones whose names I don't recognise, if we want to include all children's writers.) I know some of you don't like maths, so I'll do it for you. Fifteen out of 50 is 30%. That's not bad, is it?

I know - there are a few bestselling authors and the rest of us struggle to get contracts with deteriorating terms, and there's no space in the dwindling number of bookshops for our titles. The cheering message is that the public is still spending a lot of money on children's books. We might have to struggle to get our share of the pie, but at least the pie is still there. Given that a person reads children's books for perhaps 13 years of their life, and lives 6 or 7 times that long, having 30% of book sales go on children's books is a pretty good-sized pie.

The children's writers in the list are: JK Rowling, (Terry Pratchett), Jacqueline Wilson, Richard Parsons, Julia Donaldson, [Stephanie Meyer], JRR Tolkien, Roald Dahl, Francesca Simon, Philip Pullman, Enid Blyton, Roger Hargreaves, Daisy Meadows, Anthony Horowitz, (Katie Price), Michael Murporgo.

Thirty-five out of fifty are British. Fourteen (thirteen and two halves) of those write for children - fifteen if we include the one who writes GCSE guides. So of all the books in all the world (well, probably the English-speaking world), 15 out of 50 bestselling writers write for children and are British. (There is also Stephanie Meyer, and possibly some foreign ones whose names I don't recognise, if we want to include all children's writers.) I know some of you don't like maths, so I'll do it for you. Fifteen out of 50 is 30%. That's not bad, is it?

I know - there are a few bestselling authors and the rest of us struggle to get contracts with deteriorating terms, and there's no space in the dwindling number of bookshops for our titles. The cheering message is that the public is still spending a lot of money on children's books. We might have to struggle to get our share of the pie, but at least the pie is still there. Given that a person reads children's books for perhaps 13 years of their life, and lives 6 or 7 times that long, having 30% of book sales go on children's books is a pretty good-sized pie.

The children's writers in the list are: JK Rowling, (Terry Pratchett), Jacqueline Wilson, Richard Parsons, Julia Donaldson, [Stephanie Meyer], JRR Tolkien, Roald Dahl, Francesca Simon, Philip Pullman, Enid Blyton, Roger Hargreaves, Daisy Meadows, Anthony Horowitz, (Katie Price), Michael Murporgo.

Saturday, 6 October 2012

How to speak publisher: F is for Facebook

Has your publisher told you to have a Facebook page? Lots of writers say their publishers push them towards using Facebook/twitter/blogs/Pinterest/twatface/whatever to publicise their books. (Actually, I've not heard of a publisher who knows what Pinterest is, so we'll leave that one out.)

When (if) a publisher tells you to get a Facebook page, they don't mean invite all your cousins to be your friends and share pictures of funny kittens with you. That is not going to sell books. In fact, it will turn your mind to mush and waste your time so you write (and therefore sell) fewer books. I hate pictures of funny kittens. I can't believe so much of the world's resources are devoted to letting people laugh at photos of cats. And the time! We could cure cancer and colonise Mars if we used the time spent on funny-kitten-viewing more productively. Sorry. Anti-kitten rant over.

A publisher means you should have a page for your book/professional life, not a normal Facebook account. So - you join Facebook, you friend your friends and your family and some randomer you met on a train and your plumber, bla bla. And you post your holiday photos and links to (damnit) stupid kitten photos. But you don't friend your readers.

Please, please, don't friend your readers, especially if you write for children/young people. Because then you have to be even more careful about what you put on FB, and set up groups to keep the young readers separate from your posts about how you went on a disastrous date or you accidentally dyed your hair blue, or were sick after having too many cocktails. And don't friend your editors or your agent or your publicist (dream on) and a load of librarians and booksellers unless you are going to put time into managing lists so that you can control who sees what.

Make sure you manage your security settings so that all your private exploits are not visible to the public. It's not hard, and it's the online equivalent of not leaving your door open when you go out. And watch out for other people tagging you in photos of disreputable behaviour. Not that you engage in disreputable behaviour, of course. But if you did, untag yourself.

Once you have an account, create a page - this is the professional bit. You can create a page for you-as-author or for one of your books/series/characters. Scroll right down to the bottom of your Facebook screen and there is a link 'Create a Page'. Follow it; do as it says - I'm not doing a tutorial on creating pages (unless you really want one). On your page you can share stuff that is relevant to your book or writing life, such as links to reviews, info on events you are doing, web pages that might be interesting to your readers and so on.

People who like your work can find your page if they search for you on Facebook and can 'Like' it. You can control what they can do on your page, but it's nice to let them leave comments. Think carefully about how you are going to use your page. Are you just going to put news on it (new books, events, etc)? Or are you going to be more chatty, and put updates on your writing, projects, thoughts, blog posts, etc? Decide on your strategy and stick to it. The news approach is less work for you - but less interesting for your readers.

Your publisher will hope you will get lots of people liking your page and looking on it for information so that they can rush out and buy your next book. It's tempting to try to get lots of Likes to endorse yourself and make you feel as though you weren't wasting your time making the page. Even so, I hope you won't spam all your friends asking them to 'Like' your page. I have a strong dislike of being asked to 'like' pages for things I've not read. If you want to say you have a page, that's OK, but please don't ask me to like it. That's rather like saying - 'tomorrow is my birthday. Please buy me a present.'

From your author/book page, you can like other pages. Do it thoughtfully. If your books are for 9-year-olds, don't 'like' a page for gin or serial-killer fiction. So if you write undersea adventures, you might like pages such as 'shipwrecks' or 'sea mysteries' (I have no idea if those exist, but you get the idea). You can pretend. You could even pretend to like pages about silly kitten photos if that would appeal to your readers and fit in with your books. You can like bookshops and libraries from here with no danger of the manager of the local Waterstone[']s turning against you because you have slated their favourite holiday destination or had a row with their cousin - they can't see your personal page (as long as it's not public).

Get your publisher to 'Like' your page - it's their job to promote you. There is an important distinction here. Don't ask your friends to 'like' your page - they are your personal contacts. Do ask your professional partners to 'like' your page - your publisher/agent/local bookstore. Not other writers. We are not your publicists; we will like your page if we want to. Those of us who write reviews will probably not like your page, even if we like your work, as we might see it as a public compromise of our impartiality.

Put a link to your page in your email signature, put it on your website, your blog, your twitter profile page, your business cards (if you still have those), bookmarks and other freebies, and get the publisher to put the link on the imprint page of your books and on their publicity. After all, if they want you to do this stuff, they should support it.

If you don't want to do the kitten-sharing, cousin-hugging bit of Facebook, you can create an account and then ignore it, though you will have to collect a few friends before you are allowed to make an author page. [Purple bit changed - thanks to Mary Hoffman for the correction.] To stop people trying to friend you (they will find you, sooner or later), you can make yourself undiscoverable. Which is perhaps the ideal - you can be a as private as you like, and have the digital equivalent of a cardboard cut-out you that trollops around Facebook.

| |

| The demon that stops us getting to Mars |

A publisher means you should have a page for your book/professional life, not a normal Facebook account. So - you join Facebook, you friend your friends and your family and some randomer you met on a train and your plumber, bla bla. And you post your holiday photos and links to (damnit) stupid kitten photos. But you don't friend your readers.

Please, please, don't friend your readers, especially if you write for children/young people. Because then you have to be even more careful about what you put on FB, and set up groups to keep the young readers separate from your posts about how you went on a disastrous date or you accidentally dyed your hair blue, or were sick after having too many cocktails. And don't friend your editors or your agent or your publicist (dream on) and a load of librarians and booksellers unless you are going to put time into managing lists so that you can control who sees what.

Make sure you manage your security settings so that all your private exploits are not visible to the public. It's not hard, and it's the online equivalent of not leaving your door open when you go out. And watch out for other people tagging you in photos of disreputable behaviour. Not that you engage in disreputable behaviour, of course. But if you did, untag yourself.

Once you have an account, create a page - this is the professional bit. You can create a page for you-as-author or for one of your books/series/characters. Scroll right down to the bottom of your Facebook screen and there is a link 'Create a Page'. Follow it; do as it says - I'm not doing a tutorial on creating pages (unless you really want one). On your page you can share stuff that is relevant to your book or writing life, such as links to reviews, info on events you are doing, web pages that might be interesting to your readers and so on.

People who like your work can find your page if they search for you on Facebook and can 'Like' it. You can control what they can do on your page, but it's nice to let them leave comments. Think carefully about how you are going to use your page. Are you just going to put news on it (new books, events, etc)? Or are you going to be more chatty, and put updates on your writing, projects, thoughts, blog posts, etc? Decide on your strategy and stick to it. The news approach is less work for you - but less interesting for your readers.

Your publisher will hope you will get lots of people liking your page and looking on it for information so that they can rush out and buy your next book. It's tempting to try to get lots of Likes to endorse yourself and make you feel as though you weren't wasting your time making the page. Even so, I hope you won't spam all your friends asking them to 'Like' your page. I have a strong dislike of being asked to 'like' pages for things I've not read. If you want to say you have a page, that's OK, but please don't ask me to like it. That's rather like saying - 'tomorrow is my birthday. Please buy me a present.'

From your author/book page, you can like other pages. Do it thoughtfully. If your books are for 9-year-olds, don't 'like' a page for gin or serial-killer fiction. So if you write undersea adventures, you might like pages such as 'shipwrecks' or 'sea mysteries' (I have no idea if those exist, but you get the idea). You can pretend. You could even pretend to like pages about silly kitten photos if that would appeal to your readers and fit in with your books. You can like bookshops and libraries from here with no danger of the manager of the local Waterstone[']s turning against you because you have slated their favourite holiday destination or had a row with their cousin - they can't see your personal page (as long as it's not public).

Get your publisher to 'Like' your page - it's their job to promote you. There is an important distinction here. Don't ask your friends to 'like' your page - they are your personal contacts. Do ask your professional partners to 'like' your page - your publisher/agent/local bookstore. Not other writers. We are not your publicists; we will like your page if we want to. Those of us who write reviews will probably not like your page, even if we like your work, as we might see it as a public compromise of our impartiality.

Put a link to your page in your email signature, put it on your website, your blog, your twitter profile page, your business cards (if you still have those), bookmarks and other freebies, and get the publisher to put the link on the imprint page of your books and on their publicity. After all, if they want you to do this stuff, they should support it.

If you don't want to do the kitten-sharing, cousin-hugging bit of Facebook, you can create an account and then ignore it, though you will have to collect a few friends before you are allowed to make an author page. [Purple bit changed - thanks to Mary Hoffman for the correction.] To stop people trying to friend you (they will find you, sooner or later), you can make yourself undiscoverable. Which is perhaps the ideal - you can be a as private as you like, and have the digital equivalent of a cardboard cut-out you that trollops around Facebook.

Saturday, 29 September 2012

Don't be a Cnut

|

| Man with a spiky hat being a Cnut |

Of course there are things to be dismal about. But you know what they are, so I won't list them here - and if you don't, you can look in back issues of The Author for some ideas. Here is the only thing you need to know:

It's not going to change back. Not ever. No matter how much you whinge and whine. The past is a foreign country, and your visa has expired.

Some things are gone.

I read recently, but I can't remember where, that children won't learn to read because the libraries have computers in them instead of books. Well, obviously the libraries should have books in them. But children need to read to use the computer, so that's a stupid argument. It would be better to say children don't read because the classroom has a TV screen instead of a bookshelf. My youngest daughter learnt to read words and phrases such as All Programs, Control Panel and Instal at age 5 (alongside the usual raft of Biff and Chip books).

Reading for pleasure is not the same as reading. Learning to read doesn't need fiction, or even books - after all, children learned to read without there being fiction for them until the nineteenth century. *Of course* I'm not saying we shouldn't promote reading for pleasure, or physical books, or books for children, and it would be desperately sad if we lost these. And I *know* lots of children struggle to learn to read and need lots of help. But our preferred, current model need not be the only one that can ever work. (Indeed, we know it doesn't work that well as we are always arguing about how to improve it.)

Three in ten children in the UK own no books (four in ten for boys) - around four million children. Two thirds of American children living in poverty don't have a single book in their houses.

But nine out of ten children in the UK own a mobile phone. With cheap or free e-books, or e-book borrowing from libraries, perhaps those children will have the chance to read for pleasure, on their phones (and computers, Kindles, etc). Maybe we will have more readers, not fewer.

Yes, I know remote e-book borrowing looks bad for us, as authors (and publishers). But if something doesn't work economically, it won't last forever. If publishers don't make money from e-books because of e-book borrowing, the model will change in some way or they won't produce them any more. The system will self-correct. It might take a few years, cost a few businesses and livelihoods, but in the end something that works will emerge. We must not confuse concern for ourselves with Armageddon. Reading will not die; some publishers/writers might - different issues.

Whatever happens to the shape of publishing and the publishing industry, as writers we provide the key component - the words (the content, in newspeak). Whichever bits of the process can be done without, writing the words is the one that can't. Our words might be differently delivered, marketed, and read, but they are still needed. If you want to survive, don't stand on the beach trying to stop the tide; sit on a raft and wait to be carried by it. Don't forget to take a paddle so you have some control over where you go. We won't achieve anything by whinging and hankering after the past. But we might achieve something by being open to new possibilities.

Friday, 21 September 2012

The elephant in the writing room

"Write what you love, with no thought to whether it's what the market wants."

"Write with passion - don't worry about selling it."

How many times have we heard this? We heard it reiterated again, more than once, at CWIG (the Society of Authors Children's Writers and Illustrators' Group conference). That's all very grand and noble and swilling with creative integrity - but it's not very practical if you need to live by your writing.

It highlights the big divide in the writing community that no one ever discusses. So I'm going to invite the elephant to step out of the corner and introduce himself: the divide between those who have to live by their writing and those who can indulge in writing whatever they want because they have an independent income, accumulated riches from an earlier career, a large pension, a lottery win, an Arts Council grant, a wealthy spouse, or a 'day job'.

A very few people are able to write exactly what they want and, because it coincides exactly with what the market wants, can make a good (enough) living from it. Super. I'm *so* pleased for you, genuinely. Remember, though, that markets change. The people who sold crateloads of books a few years ago sometimes can't get a contract now. They have not become bad writers; the population has not suddenly gone off their books. It's just that what publishers want to buy changes.

Let's suppose Roald Dahl didn't die, but went into hiding. And now he submitted a book outline, under a false name, to a children's publisher. What are the chances of his book being published? Slight, I'd say. There's too much that is violent or scary for most publishers of books for 8-10s now. Fashions (and sensibilities) change.

So what about those of us who have children to feed, a house to run, and no high-earning partner willing to let us off our share of contributing to the household income? We either have a different day job, or we write other things as well - things that sell but are perhaps not our overriding passion. You could see it as a different kind of day job. I am a writer, and my day job is also being a writer.

Unless you are mega-successful or very prolific, you can't make a living just by writing what you like best. Let's suppose you are lucky enough to get a two-book deal with a £50,000 advance. (That's pretty lucky, these days.) You take a year to write each book (some people do). So that's £25,000 a year. Now give your agent 15% + VAT, which is £4,500 and we're down to £20,500, which is already less than the average wage - and expenses have to come out of that. My annual expenses vary hugely, but are never lower than £3,000 so let's use that figure. Now we're down to £17,500 a year. And you have to get this type of contract *every* two years without fail. And only if your books earn out do you get more. (Plus PLR.) Doesn't work, does it? It's a low enough income to get income support.

If you need more money, maybe you do other things, such as school visits or teaching creative writing. That's fine - but it's no more noble and filled with integrity than writing something you are less passionate about.

Enough of the hypothetical. How does it work? These are the books I have written over the last two years:

seven short vampire novels

an adult history of physics

children's non-fiction books on -

three retellings of classic stories

four picture books

So that's a total of 26. OK, some are very short. But no matter. It's still a fair number. (As we're going for full disclosure, I've also written part of a book that has several authors, done a bit of copy-editing and critiquing, been an RLF fellow, an RLF lector, taught an 8-week undergraduate summer school on creative writing, built a few websites, and made two book trailers.)

I'm not going to tell you which of those books I was passionate about, but I did draw up a table of passion-against-income for each of them. I have estimated total royalties likely and have ignored PLR, so the income bit is not wholly accurate, but it gives an idea. So, in terms of percentage of income from writing, missing out one book that doesn't have a publisher yet (but is 10 on passion) and missing out the partial book, here's the breakdown:

% of income passion rating 0-10 for book number of books in this category

22% 10 8

25% 8 6

6% 7 2

31% 5 5

13% 4 4

3% 2 1

So if I had only written books I was passionate about (and we'll go down to 8, as fairly passionate about) I would have earned half as much. Which is not enough - though I can see that if I had other money from somewhere, it would have been a very nice sum to have.

There really are two classes of writer. Those who can afford to spend years on a book and accept a tiny advance are not professional writers. They may be published, and popular, and very good - but they are recreational or part-time writers. Professional writers need to worry about margins and expenses and need to negotiate good deals with their publishers. The recreational writers are no less 'real' writers, but their position is different - and they have no right to claim moral superiority or greater integrity on account of that position. Those of us who need to earn a living are not 'selling out'. A book should be judged on its own merits, and a writer shouldn't be judged at all.

"Write with passion - don't worry about selling it."

How many times have we heard this? We heard it reiterated again, more than once, at CWIG (the Society of Authors Children's Writers and Illustrators' Group conference). That's all very grand and noble and swilling with creative integrity - but it's not very practical if you need to live by your writing.

It highlights the big divide in the writing community that no one ever discusses. So I'm going to invite the elephant to step out of the corner and introduce himself: the divide between those who have to live by their writing and those who can indulge in writing whatever they want because they have an independent income, accumulated riches from an earlier career, a large pension, a lottery win, an Arts Council grant, a wealthy spouse, or a 'day job'.

A very few people are able to write exactly what they want and, because it coincides exactly with what the market wants, can make a good (enough) living from it. Super. I'm *so* pleased for you, genuinely. Remember, though, that markets change. The people who sold crateloads of books a few years ago sometimes can't get a contract now. They have not become bad writers; the population has not suddenly gone off their books. It's just that what publishers want to buy changes.

Let's suppose Roald Dahl didn't die, but went into hiding. And now he submitted a book outline, under a false name, to a children's publisher. What are the chances of his book being published? Slight, I'd say. There's too much that is violent or scary for most publishers of books for 8-10s now. Fashions (and sensibilities) change.

So what about those of us who have children to feed, a house to run, and no high-earning partner willing to let us off our share of contributing to the household income? We either have a different day job, or we write other things as well - things that sell but are perhaps not our overriding passion. You could see it as a different kind of day job. I am a writer, and my day job is also being a writer.

Unless you are mega-successful or very prolific, you can't make a living just by writing what you like best. Let's suppose you are lucky enough to get a two-book deal with a £50,000 advance. (That's pretty lucky, these days.) You take a year to write each book (some people do). So that's £25,000 a year. Now give your agent 15% + VAT, which is £4,500 and we're down to £20,500, which is already less than the average wage - and expenses have to come out of that. My annual expenses vary hugely, but are never lower than £3,000 so let's use that figure. Now we're down to £17,500 a year. And you have to get this type of contract *every* two years without fail. And only if your books earn out do you get more. (Plus PLR.) Doesn't work, does it? It's a low enough income to get income support.

If you need more money, maybe you do other things, such as school visits or teaching creative writing. That's fine - but it's no more noble and filled with integrity than writing something you are less passionate about.

Enough of the hypothetical. How does it work? These are the books I have written over the last two years:

seven short vampire novels

an adult history of physics

children's non-fiction books on -

- maths

- aerospace engineering

- the work of charities in emergencies (eg war, famine, earthquake)

- what the world would be like after a pandemic

- fast things

- rock bands

- animals

- internet safety

- cybercrime

- the history of surgery

three retellings of classic stories

four picture books

So that's a total of 26. OK, some are very short. But no matter. It's still a fair number. (As we're going for full disclosure, I've also written part of a book that has several authors, done a bit of copy-editing and critiquing, been an RLF fellow, an RLF lector, taught an 8-week undergraduate summer school on creative writing, built a few websites, and made two book trailers.)

I'm not going to tell you which of those books I was passionate about, but I did draw up a table of passion-against-income for each of them. I have estimated total royalties likely and have ignored PLR, so the income bit is not wholly accurate, but it gives an idea. So, in terms of percentage of income from writing, missing out one book that doesn't have a publisher yet (but is 10 on passion) and missing out the partial book, here's the breakdown:

% of income passion rating 0-10 for book number of books in this category

22% 10 8

25% 8 6

6% 7 2

31% 5 5

13% 4 4

3% 2 1

So if I had only written books I was passionate about (and we'll go down to 8, as fairly passionate about) I would have earned half as much. Which is not enough - though I can see that if I had other money from somewhere, it would have been a very nice sum to have.

There really are two classes of writer. Those who can afford to spend years on a book and accept a tiny advance are not professional writers. They may be published, and popular, and very good - but they are recreational or part-time writers. Professional writers need to worry about margins and expenses and need to negotiate good deals with their publishers. The recreational writers are no less 'real' writers, but their position is different - and they have no right to claim moral superiority or greater integrity on account of that position. Those of us who need to earn a living are not 'selling out'. A book should be judged on its own merits, and a writer shouldn't be judged at all.

Monday, 17 September 2012

The Other Place

I'm over at Awfully Big Blog Adventure this morning talking about the CWIG (Children's Writers' and Illustrators' Group) conference in Reading. It's not a serious write-up. You won't find useful hints and tips on writing or fulsome praise for the speakers. Not at all.

Monday, 10 September 2012

The Internet: seducer, scapegoat or serendipity stall?

Are writers distracted from work by stuff on the web? Yes, sometimes. Do they need to pay good money for silly applications that block their access to the web. No, not unless they are total wimps and suckers.

An article in the Daily Telegraph is the latest in a string of mumblings that the internet is the enemy of creativity. Naomi Klein, Dave Eggers and Zadie Smith are apparently amongst the novelists who can't write unless they use SelfControl and Freedom (applications) to prevent them watching dumb cat videos on YouTube. Really? What's wrong with unplugging the modem, working in a cafe or library that doesn't have wifi, or even just using real self-control? After all, if they know they want to avoid messing about online, turning off the router, or just disconnecting from the network, is really not very hard to do (and it's free). I'm with Will Self, who said of this self-nannying: "“Get a grip, Zadie! I’m sorry, but that is just pathetic. Turn off the computer. Write by hand. I find that ludicrous.”

But there is another aspect. I suppose it depends in part on what you write, but I find instant access to the internet very helpful. I'm just starting a new project, and it's set in Victorian London. I'm not one of those people who does all the research and then all the writing - I'm too impatient to get started.

So I spent a day sitting in the sun making random notes on an old envelope and reading MR James ghost stories, then started writing. I probably won't keep those early pages, but they help to get the voice right. Yet writing the first 500 words I needed to check: when cigarettes replaced clay pipes in London; how long a baby will survive without oxygen at birth; which treatments of such a baby maximise the chances of its survival without ill-effects; when artificial resuscitation methods started and what they were; what the Society for Recovery of Drowned Persons recommended for treating nearly-drowned people; the appearance of a baby born in the caul; the appearance of the original Waterloo Bridge; when the toffee apple was invented (1940s - no good). I needed to know these things immediately. Guessing and writing on wouldn't work, as some of these are essential to the working out of the plot and I need to feel it's right, or at least possible. And in looking for a mudlark, I discovered there is a very unsavoury job of sewer hunter. I'll have one of those!