Sadly, after a brief flirtation with free love, I've returned the Captcha comment verification to the blog. There were not too many spam comments to start with, but they have mushroomed over the last week and far more were getting through Blogger's spam filter. I don't have time to be deleting crud from the comments all the time. Interestingly, the post that attracts by far the most spam is PLR =/= income tax (a curmudgeonly rant) presumably because PLR and income tax and search-magnets.

Scanning the spam, though, I did wonder about some of the comments. Why is the word 'fastidious' so common in them? Who ever follows those links anyway? But who in particular is going to follow a link if the comment starts off 'most of the people who comment here appear brain dead' or 'I was hoping to find something interesting here, not a lot of complaining about a problem you could do something about if you would just stop complaining'? (The latter might be appropriate to one or two of my rants, but it wasn't appropriate to the cheerful post it was attached to.)

Spam-mongers are, I suppose, the cold-callers of the blogosphere. But if I were a robot, I'd go and look for a job building car bodies or something instead of leaving comments on random blogs. (Yes, I do know it's a different type of robot. Joke. Don't flood me with comments about bots/robots and software/hardware. Especially not spam comments.)

And finally... the hits on the blog have rocketed up with captcha turned off. I suspect this means the bots are hunting out blogs without verification. So if any of you wants just numbers of hits, so that you can brag to a publisher that your blog gets 10,000 hits a month, or whatever, just turn off captcha and wait a few weeks. And if you're a publisher, and some prospective writer tells you their blog gets 10,000 hits a month, just pop along there and see if comment verification is turned on. If not, lots of those hits are from bots that won't buy a book.

So I'm very sorry about the return to the stupid letter/number reading and I know they are very hard to do. But please carry on leaving comments. As the other bots say: your comment is valuable to us so please continue to hold.

This blog started as a guide to publishing and if you look through the old stuff there's plenty of advice that is still useful. Now it's more random ruminations and pointless pontificating around publishing

Friday 30 November 2012

Wednesday 21 November 2012

The other place: Book vivisection

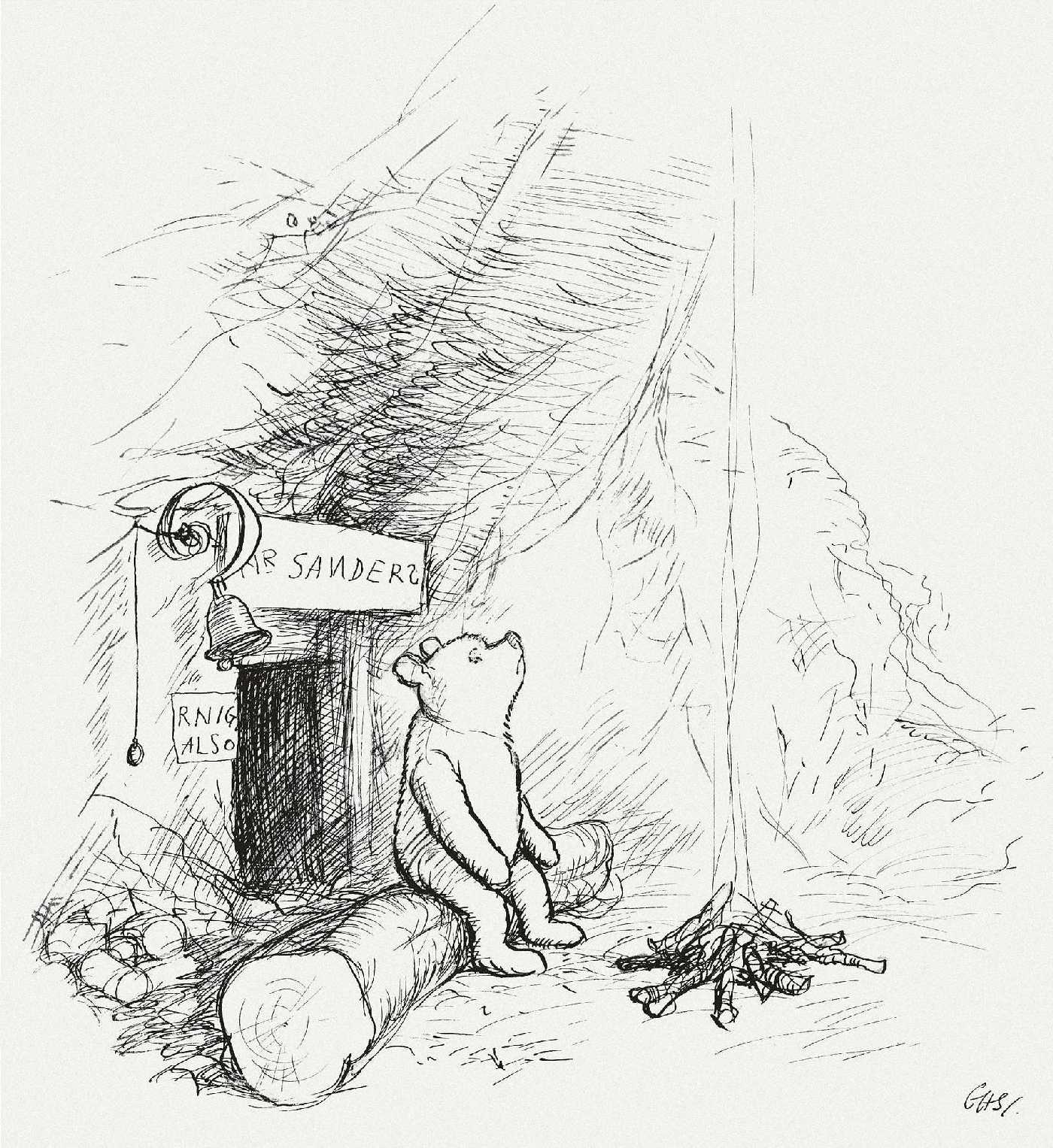

Nothing new here today, but Winnie-the-Pooh is dissected with a sharp scalpel over at Stroppy's second home, Book Vivisection.

Thursday 15 November 2012

Working premises

Today we're going to talk about premises. Not the building you write in, but the central idea behind a story.

Creative writing students and new writers often have real difficulty with identifying the premise of their story. Sometimes that's because they don't have one, or the premise is so weak it won't support much of a story. But often it's because they don't really understand what a premise is.

The premise is similar to the hook, or the one-line pitch, except the point of it is not to sell your story, but to provide its backbone.

If your story has no premise, it's like a jellyfish, just flobbling around with no direction or plan in life (apologies to jellyfish who feel undermined by this assessment of their prospects).

If it has a strong premise and everything sticks firmly to it, with no extraneous curfuffle, it's like a strong, sleek snake.

Most stories are somewhere in between, with a premise but some things (subplots, for example) which branch out from it. But they should branch - they should not float around, only held in the body of the work by the soft tissue.

This is a whale. It has a vestigial leg, the only purpose of which is to prove that evolution is true. It is not connected to the whale's backbone. Make sure your story doesn't have vestigial legs.

Some stories have a premise which doesn't really lend itself to narrative, which is a bit of a shame.

Black Beauty is an example. The premise is 'horses suffer at the hands of humans and there's nothing they can do about it.' So that sets us up with a central character who has no autonomy, but will be buffeted by fate (in the form of capricious humans) and we will just have to see whether he responds by being stalwart and heroic or by being rebellious - and more than likely sent to the knacker's yard as a consequence. It's a moral fable, and a didactic treatise on horse-management. In terms of narrative, it's a series of loosely connected episodes, of the 'and then...and then... and then...' type, some of them with an explicit moral chucked in. (Keep Sundays sacred, don't drink, etc.) This is, as Mary Hoffman pointed out to me, the structure of the misery memoir. I would add: or the saint's life. Hagiography of a horse.

Black Beauty is an example. The premise is 'horses suffer at the hands of humans and there's nothing they can do about it.' So that sets us up with a central character who has no autonomy, but will be buffeted by fate (in the form of capricious humans) and we will just have to see whether he responds by being stalwart and heroic or by being rebellious - and more than likely sent to the knacker's yard as a consequence. It's a moral fable, and a didactic treatise on horse-management. In terms of narrative, it's a series of loosely connected episodes, of the 'and then...and then... and then...' type, some of them with an explicit moral chucked in. (Keep Sundays sacred, don't drink, etc.) This is, as Mary Hoffman pointed out to me, the structure of the misery memoir. I would add: or the saint's life. Hagiography of a horse.

Some stories have a premise with strong narrative potential. The premise of The Hunger Games is that in a future dystopian society, the ruling group keep control by forcing children to kill each other in a reality TV show. The reality-TV-show element has particular resonance for our society because so many of us sit glued to reality TV shows every week, but the central idea of the child sacrifice to keep society in order is as old as the minotaur legend it draws on, and older. (Indeed, I'd say it's a version of what all societies do in trying to maintain the status quo, but that's a digression.)

If you can frame your premise as a fairly precise and interesting question that can have more than one answer,and that contains the germ of a conflict or challenge, you have a strong premise with narrative potential. So 'what would happen if a Minoan-style sacrifice were demanded of a modern/future society?' works. I'd say 'what happens if you're a horse?' is not a good premise. It's too vague, and although there are lots of specific answers, there is really only one over-arching answer, and it's that things happen to you.

A story with a strong premise can be fixed. A story with a weak premise, or no premise, is doomed (in today's market - don't write Black Beauty, it's not 1877). Work out your premise before you spend months writing the story - you might be wasting your time.

Do you know what the premise of your story is? Don't say 'it's about a boy who goes on an adventure...' That's a plot summary. What is the question that your book answers? By the way, the question will also tell you whether your book is that elusive thing, 'high concept'. What is the question, and what is the answer? That is your book, in a nutshell: the question is the premise and the answer is the plot. If there is no interesting question, or no plausible or interesting answer, you might like to think again...

Creative writing students and new writers often have real difficulty with identifying the premise of their story. Sometimes that's because they don't have one, or the premise is so weak it won't support much of a story. But often it's because they don't really understand what a premise is.

The premise is similar to the hook, or the one-line pitch, except the point of it is not to sell your story, but to provide its backbone.

|

| Moon jellyfish, Hans Hillewaert |

If your story has no premise, it's like a jellyfish, just flobbling around with no direction or plan in life (apologies to jellyfish who feel undermined by this assessment of their prospects).

|

| Snake skeletong, dbking |

If it has a strong premise and everything sticks firmly to it, with no extraneous curfuffle, it's like a strong, sleek snake.

Most stories are somewhere in between, with a premise but some things (subplots, for example) which branch out from it. But they should branch - they should not float around, only held in the body of the work by the soft tissue.

This is a whale. It has a vestigial leg, the only purpose of which is to prove that evolution is true. It is not connected to the whale's backbone. Make sure your story doesn't have vestigial legs.

Some stories have a premise which doesn't really lend itself to narrative, which is a bit of a shame.

Black Beauty is an example. The premise is 'horses suffer at the hands of humans and there's nothing they can do about it.' So that sets us up with a central character who has no autonomy, but will be buffeted by fate (in the form of capricious humans) and we will just have to see whether he responds by being stalwart and heroic or by being rebellious - and more than likely sent to the knacker's yard as a consequence. It's a moral fable, and a didactic treatise on horse-management. In terms of narrative, it's a series of loosely connected episodes, of the 'and then...and then... and then...' type, some of them with an explicit moral chucked in. (Keep Sundays sacred, don't drink, etc.) This is, as Mary Hoffman pointed out to me, the structure of the misery memoir. I would add: or the saint's life. Hagiography of a horse.

Black Beauty is an example. The premise is 'horses suffer at the hands of humans and there's nothing they can do about it.' So that sets us up with a central character who has no autonomy, but will be buffeted by fate (in the form of capricious humans) and we will just have to see whether he responds by being stalwart and heroic or by being rebellious - and more than likely sent to the knacker's yard as a consequence. It's a moral fable, and a didactic treatise on horse-management. In terms of narrative, it's a series of loosely connected episodes, of the 'and then...and then... and then...' type, some of them with an explicit moral chucked in. (Keep Sundays sacred, don't drink, etc.) This is, as Mary Hoffman pointed out to me, the structure of the misery memoir. I would add: or the saint's life. Hagiography of a horse. Some stories have a premise with strong narrative potential. The premise of The Hunger Games is that in a future dystopian society, the ruling group keep control by forcing children to kill each other in a reality TV show. The reality-TV-show element has particular resonance for our society because so many of us sit glued to reality TV shows every week, but the central idea of the child sacrifice to keep society in order is as old as the minotaur legend it draws on, and older. (Indeed, I'd say it's a version of what all societies do in trying to maintain the status quo, but that's a digression.)

If you can frame your premise as a fairly precise and interesting question that can have more than one answer,and that contains the germ of a conflict or challenge, you have a strong premise with narrative potential. So 'what would happen if a Minoan-style sacrifice were demanded of a modern/future society?' works. I'd say 'what happens if you're a horse?' is not a good premise. It's too vague, and although there are lots of specific answers, there is really only one over-arching answer, and it's that things happen to you.

A story with a strong premise can be fixed. A story with a weak premise, or no premise, is doomed (in today's market - don't write Black Beauty, it's not 1877). Work out your premise before you spend months writing the story - you might be wasting your time.

Do you know what the premise of your story is? Don't say 'it's about a boy who goes on an adventure...' That's a plot summary. What is the question that your book answers? By the way, the question will also tell you whether your book is that elusive thing, 'high concept'. What is the question, and what is the answer? That is your book, in a nutshell: the question is the premise and the answer is the plot. If there is no interesting question, or no plausible or interesting answer, you might like to think again...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)